What This Book is About

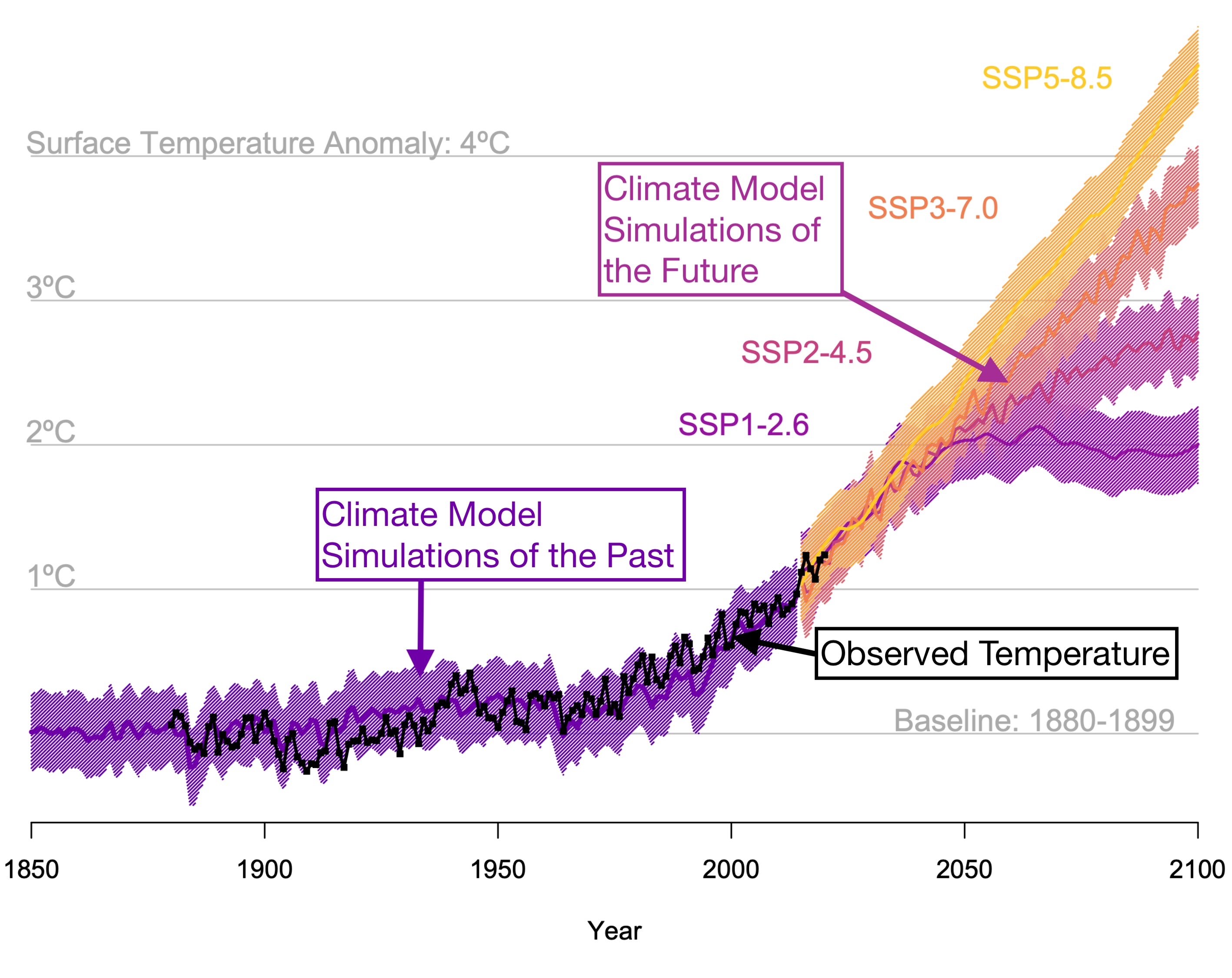

In this book we’ll discuss the ideas that you need to know to understand the science of global warming. By the end of the book you will understand the following figure in a very deep way. It’s showing three different kinds of estimates of global mean temperature: those that have been observed (black), those that are based on climate model simulations of the past (purple), and those based on climate model simulations of four potential futures (other colors).

In this figure we can see a general warming trend that begins in about the 1970s and that continues on through most or all of the 21st century; this is global warming. But there are also many details in this figure. Each chapter will explain the science of these important details. Chapter 1 explains the history of the fundamental science of global warming: what was figured out when, and by whom? Chapters 2 through 5 explain the fundamentals of the greenhouse effect and the carbon cycle; these explain why we see the trend in global warming in the figure above. Chapter 6 explains why the lines in this figure are squiggly and not smooth. Chapters 7 and 8 discuss the rationale behind how it is even possible to forecast global climate conditions a hundred years into the future (the four colored lines) and what kind of warming response we might expect to occur based on fundamental principles. Chapters 9 and 10 explain how climate models and their forecasts for the future work. In the last two chapters we learn about the major risks of global warming and some of the solutions we could implement.

How This Book Works

The format of this book may be fundamentally different from any book you’ve read before. It interweaves a reader-interactive interface within the texts that helps you to remember what you read. Think of it as a book with an embedded, sophisticated flash-card system that can guarantee you will remember what you read permanently.

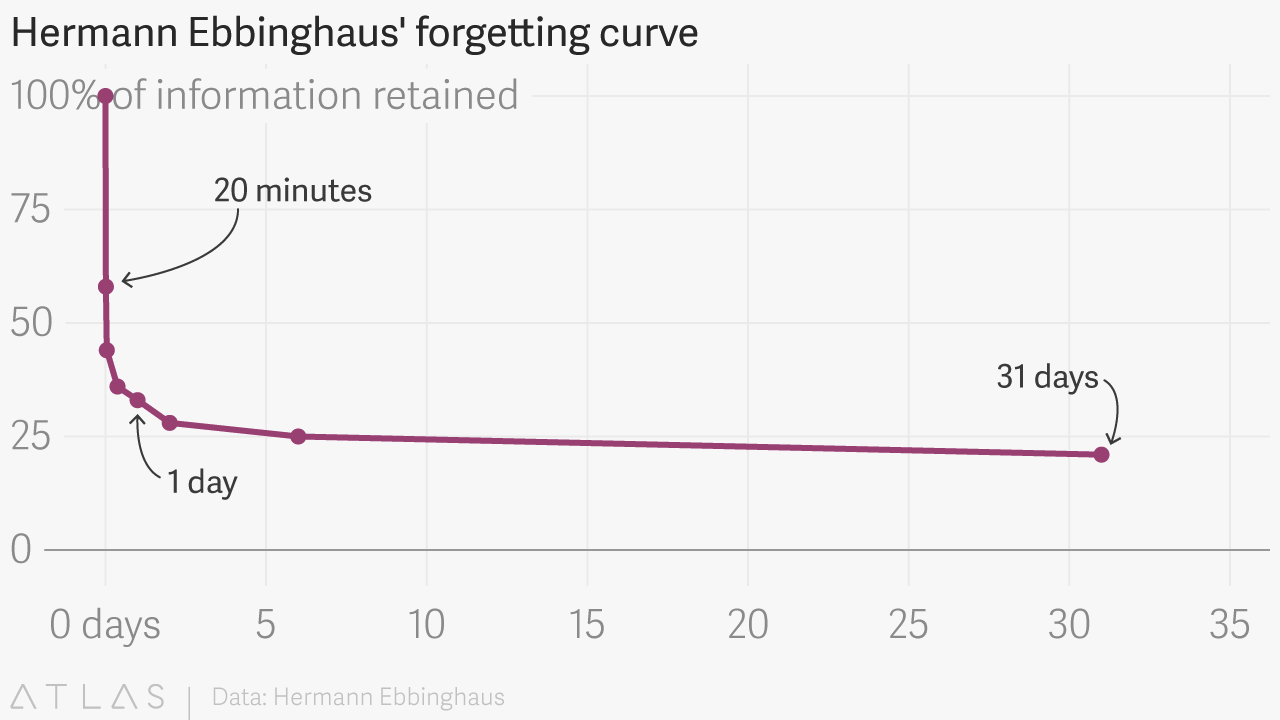

The way that nearly all people read books is broken. It amounts to a spectacular waste of time because we forget what we read, almost immediately. The first psychologist to study this forgetting effect empirically was Hermann Ebbinghaus, who ran a series of memory tests on himself in the 1880s. Ebbinghaus, H. (1964). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology (H. A. Ruger and C. E. Bussenius, Trans.). New York: Dover. (Original work published 1885). His results can be summarized with this figure:

You can see in the figure that after initially learning some facts or ideas, within 20 minutes of learning them, we already have forgotten nearly half of them. Within a few days, we will forget nearly 75% of them, and given several months we will have forgotten nearly everything as the curve approaches zero. This ‘Ebbinghaus forgetting curve’ has been replicated by other scientists many times over the past century.

In some ways this forgetting curve represents a best-case scenario because it is for a focused learning situation, with easily understood pieces of information. When we read a book that we only partially understand and in unfocused conditions, this curve is too optimistic and we remember even less. So what are we to do about this?

One option would be to follow the approach of the inventors of the book: institute a cycle of re-readings. The ancient world in which books were invented was radically different than our own. Books were extremely rare and spectacularly expensive. Ancient peoples also understood the fallibility of our memories. So books were not simply read once and put down, but rather read over and over again, in cycles of re-reading. This approach is still maintained in many religious communities, where sacred texts are read in an annual cycle of scheduled re-readings. This meant that while people who lived prior to the invention of the printing press may have read (or more likely heard read out loud to them) at most only a few books, they knew them very well.

While we could follow this re-reading approach, it turns out that there is a far more efficient way to remember what we read and learn. Much of the text that follows is closely based on Michael Nielsen’s explication in Quantum Country For more than a century, cognitive scientists have studied human memory. And they’ve figured out some simple strategies that can ensure that we will remember something permanently. The single most important of these ideas is to re-test us on our knowledge, with expanding time intervals between tests.

As an example, consider the question: ‘In Earth’s atmosphere, what is the strongest greenhouse gas?’ If you are tested on this question and get it right (‘Water vapor’), you’d ideally be tested again in a few days. And if you got it right again, you’d be tested again a few weeks after that. And so on, following a gradually expanding schedule. If you get the question wrong on one of those tests, the schedule would contract, so you can relearn the answer.

It turns out that such an expanding schedule is the optimal way to retain information because it exactly counteracts the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. Each time you’re re-tested, your brain consolidates the answer a little better into long-term memory, until eventually it’s permanent.

Spaced-repetition testing Nicky Case’s How To Remember Anything Forever-ish delightfully introduces more ideas about spaced repetition testing through an interactive comic. is a simple idea, but it has profound consequences:

First, it doesn’t take much overall time. Because of the expanding test schedule, it typically only takes a few minutes of total review time to memorize something for decades. I won’t go through the math showing that, but you can see it worked out elsewhere. Gwern Branwen and Michael Nielsen, among others, have worked this out theoretically. You can also see it empirically in data that’s stored in a spaced-repetition program like Anki.

Second, spaced-repetition testing gives you a guarantee that you will remember the answer to a question. For the most part our memories work in a haphazard manner. We read or hear something interesting and hope that we remember it in the future. Spaced-repetition testing makes memory into a choice.

These facts are truly incredible news and are worth repeating: you can guarantee that you will remember any fact for decades for the price of a few minutes of well-timed review practice. Prior to the invention of the computer, a physical spaced-repetition reviewing process required quite a bit of discipline and a well-structured set of index cards and boxes. See for example how a Lietner Box works. Fortunately for us, now a computer program can handle all the scheduling.

Which brings us back to this book. It’s a collection of texts on the science of Global Warming with interleaved quiz-like questions that are based on a spaced-repetition program called Orbit. The idea is that you will create a free account with Orbit and then read the texts, answering questions as you go along.

Ultimately, this all does come with an additional time cost: you’re committing to future question reviews. But consider what that buys you. Each chapter of this book will take you perhaps one or two hours to completely read. In a conventional book, you’d forget most of what you learned over the next few weeks, retaining a handful of ideas if you’re lucky. But with spaced-repetition testing built into the medium, a small additional commitment of time means you will remember all the core material of the book. Doing this won’t be difficult, it will be easier than the initial read. Furthermore, you’ll be able to read other material that builds on these ideas; it will open up an entire world.

This spaced-repetition approach is why the questions only require a few seconds to read and answer. They’re not complex exercises, in the style of a textbook. Rather, the questions have a different point: the promise each question makes is that you will remember the answer forever. It’s to permanently change your thinking.

After you set up an account with Orbit, your review schedule for each question in the book will be tracked, and you’ll receive periodic reminders containing a link which takes you to an online review session. That review session isn’t the full book. It is just like quickly answering flash-card questions. Each review session contains only the questions that are ‘due’, so you can quickly run through them. The time commitment will usually be a few minutes per session, with a little more time early on, when questions need frequent re-testing, but rapidly dropping off after that. You can even do the reviews on your phone while grabbing coffee, or standing in line, or in transit.

Here are a couple things to keep in mind about the Orbit questions within the text:

Don’t worry about getting questions wrong! You are not graded here for wrong answers. Getting a question wrong helps you to diagnose what you do and don’t know. And it’s important to use this information to help you fill your knowledge gaps as rapidly as possible. Getting questions wrong or even just thinking carefully about each question thus has enormous benefits over a straight-through reading of the text.

Some of the questions might appear as though they are repeated, but they are not! What is going on is that many of the cards reverse the content of the original question. Consider the example question we discussed before: ‘In Earth’s atmosphere, what is the strongest greenhouse gas?’ Answer: ‘Water vapor’. When you learn this question you are actually only learning it in one direction. Your brain is learning only a one-way connection between the answer of ‘water vapor’ and the question of ‘what is the strongest greenhouse gas’. But if you need to know reasons that water vapor is important, you will have a very difficult time coming up with the fact that water vapor is the strongest greenhouse gas. This is why in addition to learning the previous question, you will also be prompted with a question like: ‘How important is atmospheric water vapor for the greenhouse effect?’ Answer: ‘It is the strongest greenhouse gas’.